Structuring Chinese history: Diwang tu 帝王圖, nianbiao 年表, ‘Chinese dynasties’ charts, and paradigmatic crisis in Chinese historiography

Speaker: Dr. James Millward (Professor of Inter-societal History at the Walsh School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University)

Topic: Structuring Chinese history: Diwang tu 帝王圖, nianbiao 年表, ‘Chinese dynasties’ charts, and paradigmatic crisis in Chinese historiography

Moderator: Dr. Ren-yuan Li (Associate Research Fellow, IHP, Academia Sinica)

Date: June 18 (Wednesday), 2025, 3:30 p.m.

Venue: Conference Room 703, 7th Floor, Research Building, IHP, Academia Sinica

Organizer: History Department, IHP, Academia Sinica

Remarks:

1. The talk will be given in English. Registration is not required. All are welcome to attend.

2. Participants who are experiencing a fever and/or respiratory symptoms are recommended to wear a face mask.

3. Please do not video, record, or make public the images and contents of the lecture without prior consent.

Contact: Ms. Luo, (02) 2782-9555 ext. 351

Summary:

Why do we (including scholars writing and teaching in European languages) organize Chinese history around "dynasties"? It seems natural to periodize according to units like Zhou, Qin, Han, Sui, Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing, but for few other places in the world do we periodize so invariably according to ruling families. Moreover, these names of "dynasties" in China are not, in fact, the names of ruling families, nor do they represent all the polities present in east Eurasia at the various eras. When Europeans first encountered Chinese history, they were confused that each ruler seemed to change the name of the country upon coming to power. "Dynasty," moreover, while seemingly a close translation of chao 朝 or dai 代,is also used to translate a variety of other Chinese terms, including nianhao 年號,jiyuan 紀元,shi 世 and even guo 國 referring to imperial reigns, imperial succession, time periods, countries and state power.

The first histories and pedagogical materials (like charts and tables) presenting China to Europe were based on the annals-type chronological histories, including Sima Guang's Zizhi tongjian and Zhu Xi's Tongjian Gangmu--but for convenience sake, Europeans often consumed these works through abbreviations and simplifications in the form of nianbiao chronologies. As summary historiography and chronological structuring of Chinese historiography was transferred to European languages and formats, did the idea of "dynasty" is it spread in the west from the 18th century convey the same meaning and serve the same function as in Ming and Qing materials? Or might an ideological message have been smuggled into Western language historiography of China?

Lastest Events

-

SpeakerStephen Sawyer

Toward a Genealogy of the Modern Demos: Democratic Society and the Problem of Public Authority in the Nineteenth Century

Time2026-03-02

Location研究大樓703室

-

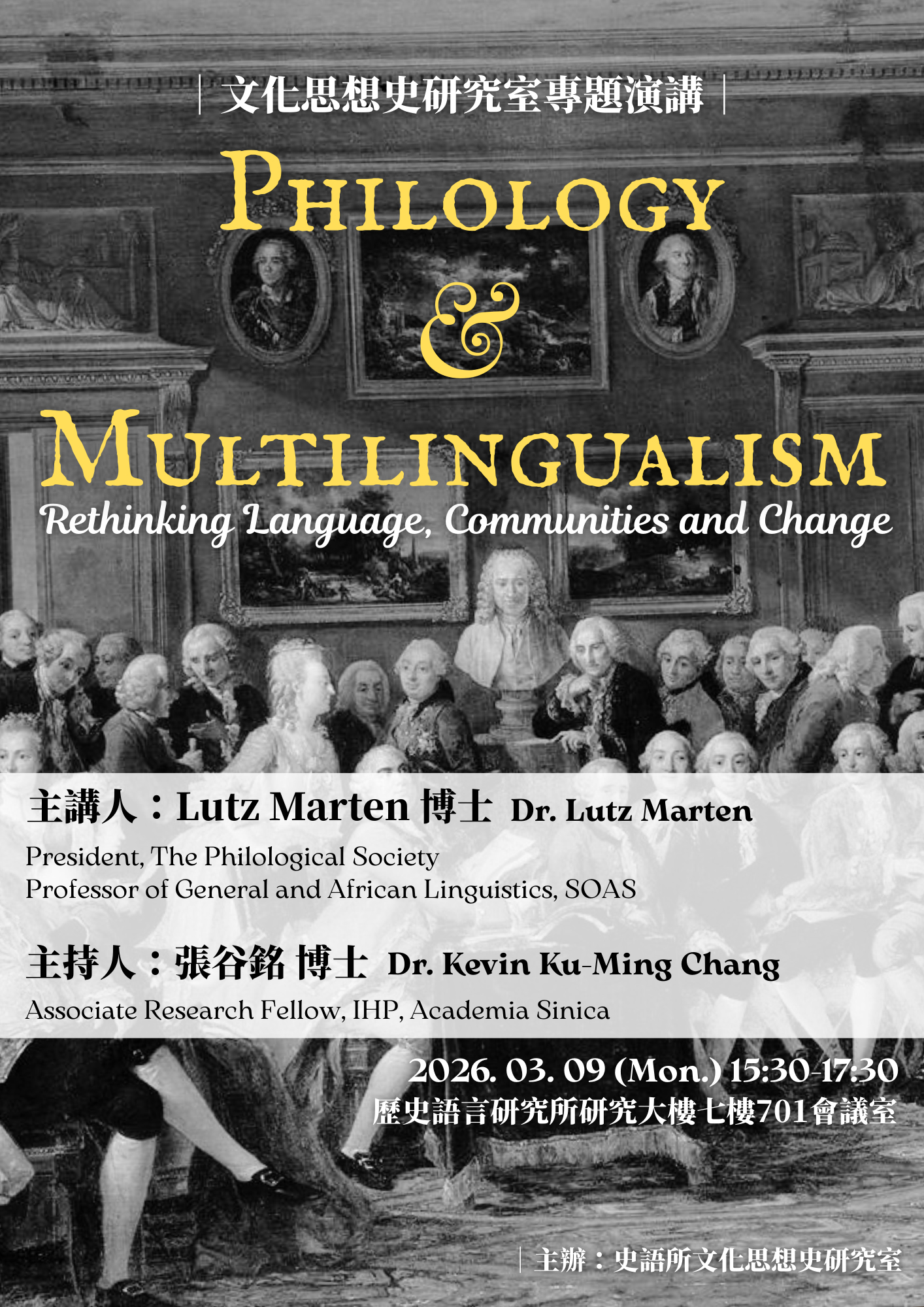

SpeakerLutz Marten

Philology and Multilingualism: Rethinking Language, Communities and Change

Time2026-03-09

Location研究大樓701室

-

Speaker鄧小南

Rediscussing the Move Toward a “Living” Institutional History: Song Dynasty Studies as a Case

Time2026-03-17

Location文物館5F會議室

-

Speaker大知聖子

Analysis of Social Networks Based on Similarities in Poetry Parts of Northern Wei Epitaphs — Using Text Mining Techniques

Time2026-03-17

Location研究大樓702室